In India, Kumbh Mela is a sweet treat for Allahabadis- and Modi's BJP

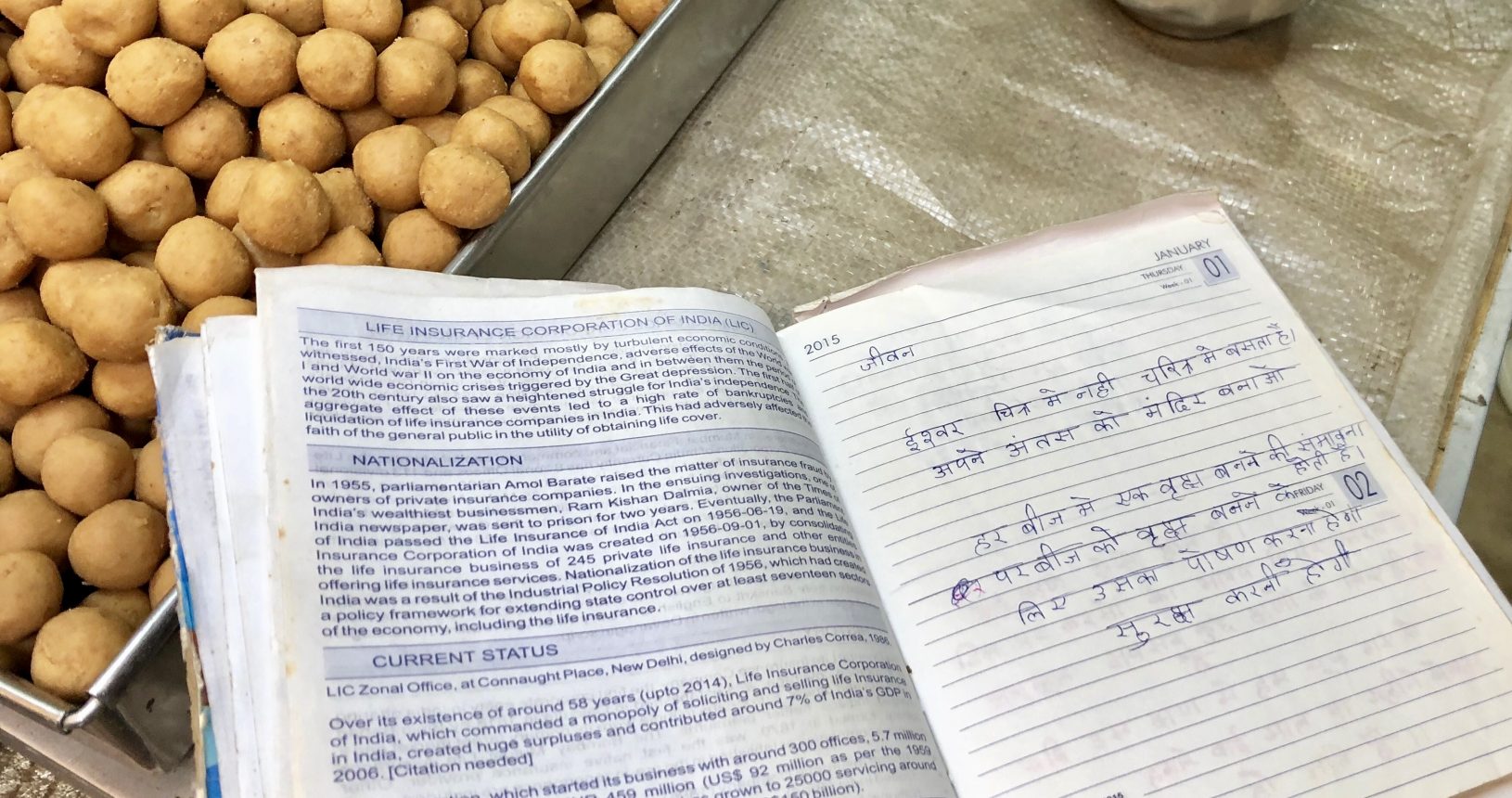

“Work is worship,” says Shrikanth Porwal. A busy 58-year-old sweet-seller from the historic city of Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh, he brushes off my question about temple-going. Instead, he shows me his notebook and a handwritten verse:

God lives in character,

not in pictures

Make your inner temple

He’s a Hindu from the Baniya caste. It’s an upper caste: wealthy traders, influential but relatively small – there’s an estimated 28 million of them across the Republic. They are also among the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s core supporters.

Still, Shrikanth is a lovely man. He is not tall but is barrel-chested, and flashes a beatific smile as he hands out boxes of koya, peda and barfi to the shoppers at his stall.

His shop, little more than a hole in the wall, is in the Chowk, the city’s traditional market, a maze of roads and lanes that grows ever more hectic as the sun sets. There are motorbikes, hand-drawn carts, trucks, rickshaws, cars and buses, not to mention tens of thousands of pedestrians and a handful of stray cows.

The noise is almost unbearable. A constant barrage of horns and klaxons: “I drive therefore I beep.” It’s as if every square inch is occupied or fought over. This is the heart of the Ganges plain: vast, lush and densely populated.

If Uttar Pradesh were a country, it would be more populous than Brazil or the combination of Germany, France and Britain. Allahabad, however, isn’t the state capital, that’s Lucknow to the north.

Situated in Uttar Pradesh’s southeast, it’s very much the state’s intellectual hub. There’s the prestigious, 132-year-old Allahabad University and the largest high-court complex in Asia – the main reason why the celebrated, lawyerly Nehru-Gandhi clan made the city their home.

But it’s Allahabad’s geographical location – wedged between the Yamuna and Ganges rivers – that invests it with enormous spiritual weight. Indeed, every 12 years, in the agricultural low season, some 120 million adherents gather for the Kumbh Mela, bathing at the Triveni Sangam – the confluence of these two rivers and a third, the mythical Sarasvati – to wash away their sins.

Shrikanth has been a regular visitor, though strictly speaking the six-yearly iteration known as the Ardh Kumbh (or half Kumbh) is a more modest affair. But with an election in the offing, this year’s Ardh Kumbh has been upgraded. Grander in scale than any previous gathering and lavished with some US$589 million in government funds, the event has become slick, people-friendly and corporatised: in short, a superb vote-getting exercise and classic Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

“It is the pride of Allahabad,” the sweet-seller asserts. He concedes it may have been politicised this year, but he still adds that “it’s much better organised than before”. “This shows that the government knows how to prioritise – which is why all of us will vote for BJP.”

Walking around the Kumbh the next morning, it’s hard not to agree with Shrikanth. In a country notorious for congestion, the attention to detail – the public toilets, the discreet crowd control, the food courts and stadium-scale lighting, not to mention the freshly laid straw on the sandy riverbanks to make walking that much easier – was almost disconcerting.

But with Uttar Pradesh sending 80 elected representatives to the Lok Sabha (or lower house of Parliament), both Allahabad and the Kumbh Mela have taken on a heightened importance this year – all the more so since Modi’s constituency, in the holy city of Varanasi, is just three hours to the east.

Indeed, no party can realistically expect to rule India without support from Uttar Pradesh. Back in 2014, the BJP, benefiting from a divided opposition, won a staggering 71 seats in the Hindi-speaking state.

But 2019, notwithstanding the Kumbh’s successes, will be different. The BJP will face stiff competition from the state’s Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP)-Samajwadi party (SP) alliance. In the last election, the SP won five seats and the BSP none despite both parties having dominated the state for the past 15 years or so.

The two parties appeal to different groups, with the BSP – led by former Uttar Pradesh chief minister Mayawati – drawing on the Dalit community and the SP counting on support from the middle castes and Muslims. If the alliance is successful, they should form a nearly invincible voting bloc.Recent Articles